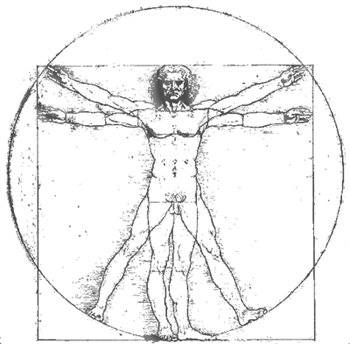

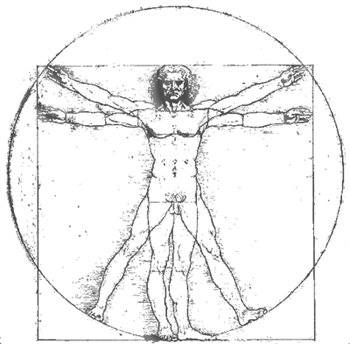

The 'Vitruvian Man' is a famous drawing with accompanying notes by Leonardo da Vinci made around the year 1492 in one of his journals. It depicts a naked male figure in two superimposed positions with his arms and legs apart and simultaneously inscribed in a circle and square. The drawing and text are sometimes called the Canon of Proportions or, less often, Proportions of Man. It is on display in the Gallerie dell' Accademia in Venice, Italy.

This image provides the perfect example of Leonardo's keen interest in proportion. In addition, this picture represents a cornerstone of Leonardo's attempts to relate man to nature. Encyclopaedia Britannica online states, "Leonardo envisaged the great picture chart of the human body he had produced through his anatomical drawings and Vitruvian Man as a cosmografia del minor mondo (cosmography of the microcosm). He believed the workings of the human body to be an analogy for the workings of the universe." It is also believed by some that Leonardo symbolised the material existence by the square and spiritual existence by the circle. Thus he attempted to depict the correlation between these two aspects of human existence.

According to Leonardo's notes in the accompanying text, written in mirror writing, it was made as a study of the proportions of the (male) human body as described in a treatise by the Ancient Roman architect Vitruvius, who wrote that in the human body:

- a palm is the width of four fingers

- a foot is the width of four palms

- a cubit is the width of six palms

- a man's height is four cubits (and thus 24 palms)

- a pace is four cubits

- the length of a man's outspread arms is equal to his height

- the distance from the hairline to the bottom of the chin is one-tenth of a man's height

- the distance from the top of the head to the bottom of the chin is one-eighth of a man's height

- the maximum width of the shoulders is a quarter of a man's height

- the distance from the elbow to the tip of the hand is one-fifth of a man's height

- the distance from the elbow to the armpit is one-eighth of a man's height

- the length of the hand is one-tenth of a man's height

- the distance from the bottom of the chin to the nose is one-third of the length of the head

- the distance from the hairline to the eyebrows is one-third of the length of the face

- the length of the ear is one-third of the length of the face

Leonardo is clearly illustrating Vitruvius De Architectura 3.1.3 which reads:

The navel is naturally placed in the centre of the human body, and, if in a man lying with his face upward, and his hands and feet extended, from his navel as the centre, a circle be described, it will touch his fingers and toes. It is not alone by a circle, that the human body is thus circumscribed, as may be seen by placing it within a square. For measuring from the feet to the crown of the head, and then across the arms fully extended, we find the latter measure equal to the former; so that lines at right angles to each other, enclosing the figure, will form a square.

There is of course no such thing as a universal set of proportions for the human body. The field of anthropometry was created in order to describe these individual variations. Vitruvius' statements may be interpreted as statements about average proportions, or perhaps as descriptions of an ideal human form. Vitruvius goes through some trouble to give a precise mathematical definition of what he means by saying that the navel is the center of the body, but other definitions lead to different results; for example, the center of mass of the human body depends on the position of the limbs, and in a standing posture is typically about 10 cm lower than the navel, near the top of the hip bones.

Note that Leonardo's drawing combines a careful reading of the ancient text, combined with his own observation of actual human bodies. In drawing the circle and square he correctly observes that the square cannot have the same center as the circle, the navel, but is somewhat lower in the anatomy. This adjustment is the innovative part of Leonardo's drawing and what distinguishes it from earlier illustrations. He also departs from Vitruvius by drawing the arms raised to a position in which the fingertips are level with the top of the head, rather than Vitruvius's much higher angle, in which the arms form lines passing through the navel.

The drawing itself is often used as an implied symbol of the essential symmetry of the human body, and by extension, to the universe as a whole.

It may be noticed by examining the drawing that the combination of arm and leg positions actually creates sixteen different poses. The pose with the arms straight out and the feet together is seen to be inscribed in the superimposed square. On the other hand, the "spread-eagle" pose is seen to be inscribed in the superimposed circle.

(From wikipedia.org)